American Art, 1800 to 1945

The core of the Museum’s collection was built by E. B. and Margaret Crocker and featured contemporary views of California during the Gold Rush. Works include early paintings of the Sierra Nevada and scenes of life in the West, more traditional still lifes and interior views, Impressionist depictions of the California’s iconic landscape, and precursors to modern art in the Golden State.

About the American Art, 1800 to 1945 Collection

Physically isolated by distance and topography from the art world of the East Coast, California art has attained a distinct regional character. This does not imply, however, that California’s artists have been unaware of national and international aesthetic movements or trends, since historically a vast number of the Golden State’s artists were transplants from other parts of the country or world. Many also perfected their craft by training elsewhere and putting their new skills to use in painting the state’s agricultural bounty, architecture, people, activities and, most often, landscape. This range of subjects created a new art and helped shape artistic identities. Taken together, the works mirror the variety of California itself.

California’s art history begins with work made by Indigenous people, and at the Crocker Art Museum this story is best told through baskets, a functional and aesthetically creative art form for which Native Californians are internationally known. As new visitors and immigrants arrived in California from other states and countries, artists began to depict people, towns, and terrain, generally through illustrations, which were made before and during the Gold Rush, when newly arrived explorers and settlers sought to show the rest of the world what life was like in California.

California landscape paintings began to take center stage a decade after the dust from the Gold Rush had settled, and in the ensuing decades these works hung in mansions newly built by gold and silver kings, real-estate moguls, bankers, and those who helped connect the country through railroads, the latter including E. B. Crocker and his wife, Margaret. The Crockers purchased iconic paintings from California’s then-contemporary artists, their acquisitions including genre scenes, still lifes, and landscapes. Most California artists at this time made landscape paintings that celebrated nature’s grandeur through awesome panoramic views of the Sierra Nevada, the paintings expressing a pride and optimism that matched the expansiveness and lofty ambitions of the age. These works also demonstrated a close communion between the artists and nature, with California depicted as a natural paradise.

Scenes like these set the tone for California art until the late 1870s, when some artists began to look to France’s Barbizon painters for inspiration. These artists depicted quiet, intimate views of nature and scenes of humanity working in harmony with the land, which in turn prompted California artists to shift their focus from views of the Sierra and prominent natural landmarks to views of more humble terrain. These paintings captured nature’s underlying mystery and spirituality, and the artists’ use of light, especially, became a transcendental metaphor for God’s presence.

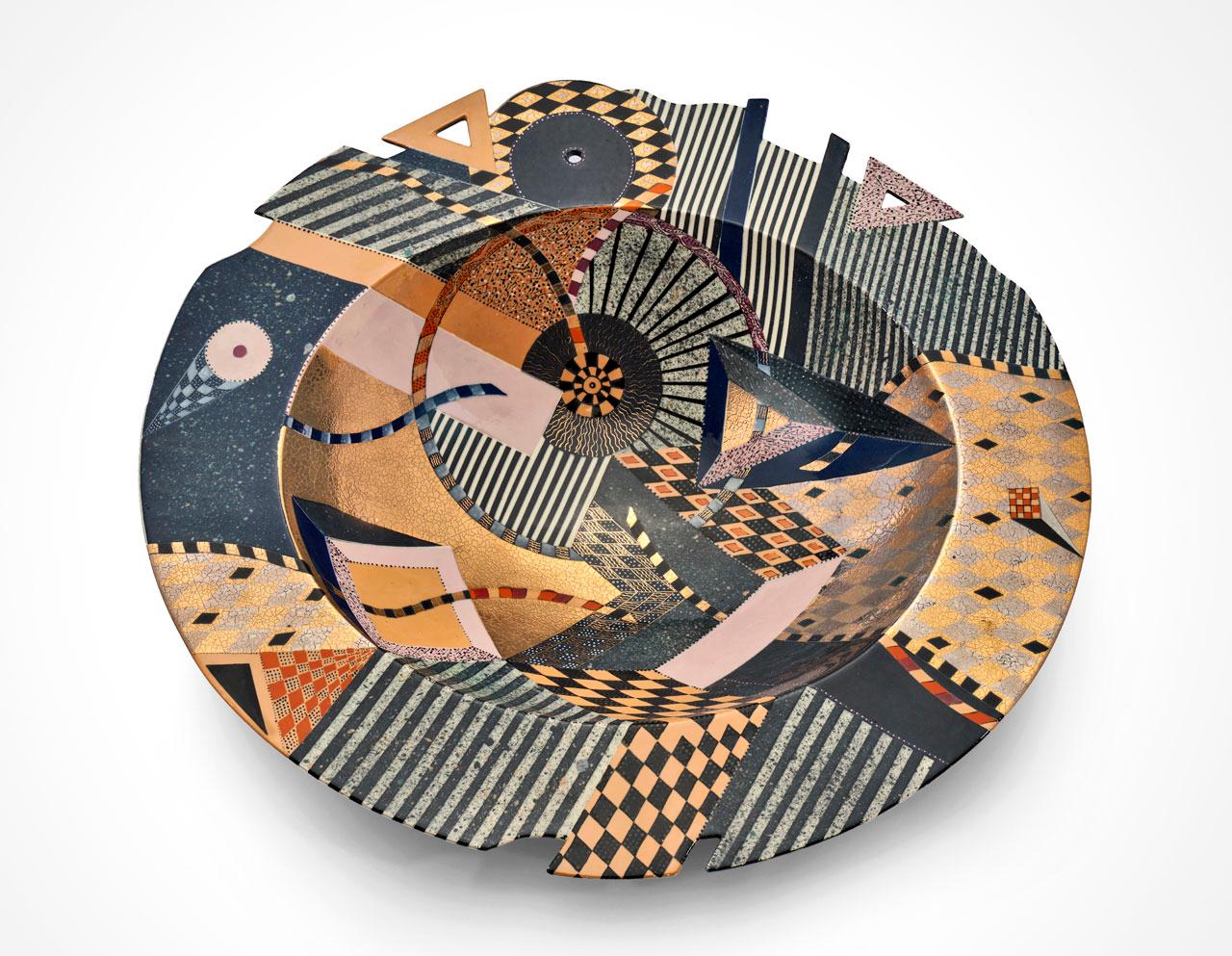

Light was also critical to the California Impressionists, a few of whom began working in California in the 1890s. Once Impressionism took hold in California, the style proved broadly popular and long-lived, as it seemed an appropriate means of capturing California’s climate, terrain, color, sunshine, and identity. Like Impressionists elsewhere, Californians made their art modern through light, color, and broken brushwork, though many of their subjects—the Sierra, rolling hills, expressive trees, the coast, and the sea—were not appreciably different from those of previous generations of artists. Also during this period, an increasing number of artists began to turn their attention to sculpture, which began to grace civic spaces, private homes, and gardens. The ideals of the turn-of-the-century Arts and Crafts movement inspired other artists to turn decorative objects and furniture into functional works of art.

Impressionism remained popular into the 1920s, past its heyday elsewhere. By this time many artists had already started to create views of modern life and people in styles influenced by European modernism. This set the stage for a new generation of artists working during the Depression era of the 1930s and early 1940s, many of whom departed from the previous generation’s idyllic representation of the land. Now, in settings both rural and urban, California artists evidenced not only the state’s charms, but its maladies, with imagery focused on people—especially laborers, the poor, and the marginalized—along with their activities, contemporary modes of transportation, and other subjects close at hand.